The 1995 Dead Man Walking soundtrack with Eddie Vedder and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan has long been a favorite, especially the two songs “The Face of Love” and “The Long Road.” I sat down recently to pick out the melodies in “The Face of Love,” and noted many interesting things about the way it weaves. I don’t know much about ragas, but I think it may be based on a Hindustani devotional raga. I heard it again recently in the series based off of the book Shantaram, where the hero meets the grandfather-gangster Khaderbhai in a music lounge, and is invited to listen to music on the theme of love.

Here is the song “The Face of Love”

It’s in the key of D, and can be played with the lead guitar in drop D.

In Western terms, we could say that the opening melody is in D lydian, using:

D – E – F# – G# – A – B – C#

But as soon as the vocals come in, it switches to D mixolydian:

D – E – F# – G – A – B – C

It’s in mixolydian for two verses, and then switches back to lydian for two verses:

Then it flats the third in a pronounced and dramatic way heard sometimes in this kind of music, and ends the phrase by coming from not one but two notes below the tonic:

There are different ways to approach this musically if one wants to build on it for future work…

One of the ways I like to look at it is mixing the idea of ragas and differing ascending-descending Western melodic approach. So we could say this is a scale that is lydian up and mixolydian down:

Or lydian up and dorian down:

In both approaches, we have in a certain sense sharps going up and flats going down.

Another way is to just remind ourselves that in whatever scale we play, the notes are flexible. The most common approach with this is in how the seventh/leading tone of major and minor scales is often changed. In natural minor, it at any time might be raised (harmonic minor), and in ionian/major it is often flatted (mixolydian).

But essentially all of the tones of any scale are flexible, and playing with them yields their unique sounds in contrast to the notes played before and after them. This is how we come up with so many different flavors. A clever musician can blend them in ways where the audience doesn’t even recognize the shifts, while at the same time knowing how and when to make the shifts stand out, like emphasizing flattening the third how the songs mentioned earlier do.

Another way to take that “all notes are flexible” approach is to get to know the different flavors of different scales, and switch back and forth between them while playing, even blending them together. This is one of my favorite ways to play, and yields all sorts of interesting adventures.

To recap:

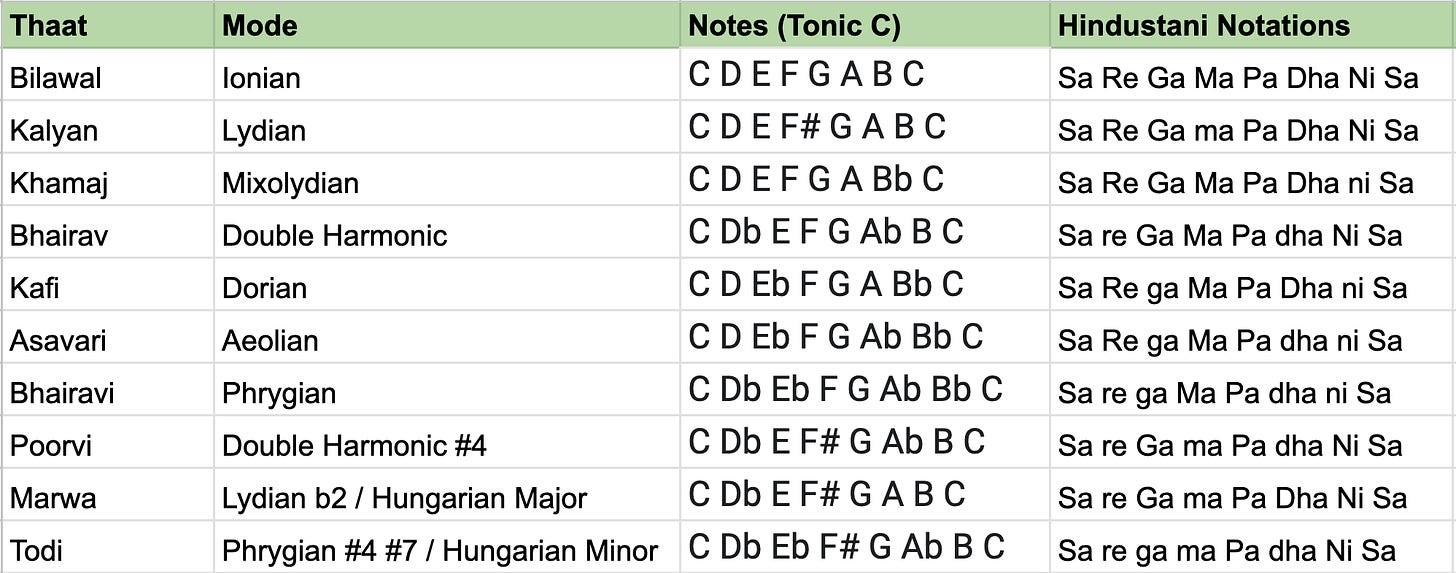

On ragas, if one is so inclined, this page on Classical Weekly talks about the thaat system that was developed to try to simplify the underpinnings of ragas, and is relatable to Western scales. It includes a table of the ten thaats and their corresponding Western scales:

And this page from Raag Hindustani talks briefly about seven ragas, their origin and feel, as well as displaying the ragas in Western notation and giving an example song each, which is pretty cool. Looking at them, you can see that ragas are more like basic scale melodies than scales. In a certain way a person could perhaps say that they are like Jazz standards–they are the bones for melodies and song making, musicians learn them and then together they improvise over and around them.